THEY ARE RISING UP! Minimizing (or maximizing) human error through reinforcement learning algorithms

Reinforcement learning algorithms are fascinating. They are smarter than models from the more popular branches of machine learning, because they do not necessarily need humans to input training data. They learn by themselves (or at least more autonomously). In order to do so, they have to be able to interact with their environment in a trial-and-error fashion. Take the famous AlphaGo Zero model (Silver et al., 2017). No one told it what good moves in the game are. No one even showed it data from past games. It has become better than any human will ever be, simply by playing, losing, and learning.

Human errors in a board game are not usually tied to extreme risks or dangers. However, in industrial, traffic, or medical settings, human inattention or incompetence can come with a high price. I think reinforcement learning models can contribute to the safety in such settings by uncovering human weakspots. Just like it does in board games.

I started building the code blocks necessary for building such a system. Because I was too lazy to keep interacting with the model myself until it learned my weakspots, I also wrote a “human simulator” based on fairly naive psychological assumptions. The task of this “human” is to receive and process information from an industrial system and to decide correctly, and as quickly as possible, whether an alarm should be triggered. This seemed like a pretty generalizable scenario.

The human struggles when they receive different types of information in quick succession, when the information is seemingly contradictory, or when there was a relaxing pace in the previous interactions. After probing and observing the (fairly simple-minded) human for a while, the reinforcement learning model detects which scenarios elicit the poorest reaction times or even wrong reactions.

You can see in the graph below that the model (i.e., the “agent”) knows which inputs are easiest for the human (darker colors) and which inputs appear the most challenging (brighter colors). The details of this tabular scenario representation are not so important, but can be understood from the full description of the project (link below). A nice result was that the model learns to make short-term sacrifices and lures the human into a false sense of security, before exploiting the rising inattention in later interactions.

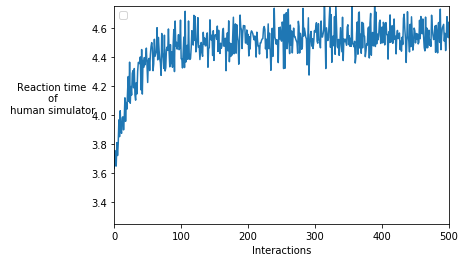

In the next plot, we can also see that, over time, the model is increasingly able to exploit the human’s weakpoints and trigger higher reaction times. Knowing which scenarios are most challenging to humans would now allow us to redesign the system or implement safeguards.

All in all, I think that smart models are ready to “stop playing games” and become more prevalent in supervising (and protecting) human operators, who are unwilling to be replaced alltogether.

If you are interested, please check out the full text here: Tutorial

Ref: Silver, D., Schrittwieser, J., Simonyan, K., Antonoglou, I., Huang, A., Guez, A., … & Hassabis, D. (2017). Mastering the game of go without human knowledge. Nature, 550(7676), 354-359.